Planting Roots Along the Walla Walla

Look around and try to imagine what this area looked like to the Tribal people who resided here for millennia and the pioneer immigrants who eventually made land claims and started farms. No roads, powerlines or buildings. Grassy meadows and rolling hills. Clear, bubbling creeks and tumbling rivers, shaded by brush and trees along their shores. Mountains stand in the distance, promising to deliver snowmelt through summer to fill streambeds and rivers. The mild microclimate appealed to the Cayuse band who wintered here and later sealed the deal for people looking for land on which to start a new life.

Agriculture continues to be the major industry in the Milton-Freewater area, with a more recent thriving wine and wine grape component and the accompanying growth in tourism services. Fruit and wheat still account for a large percentage of crops.

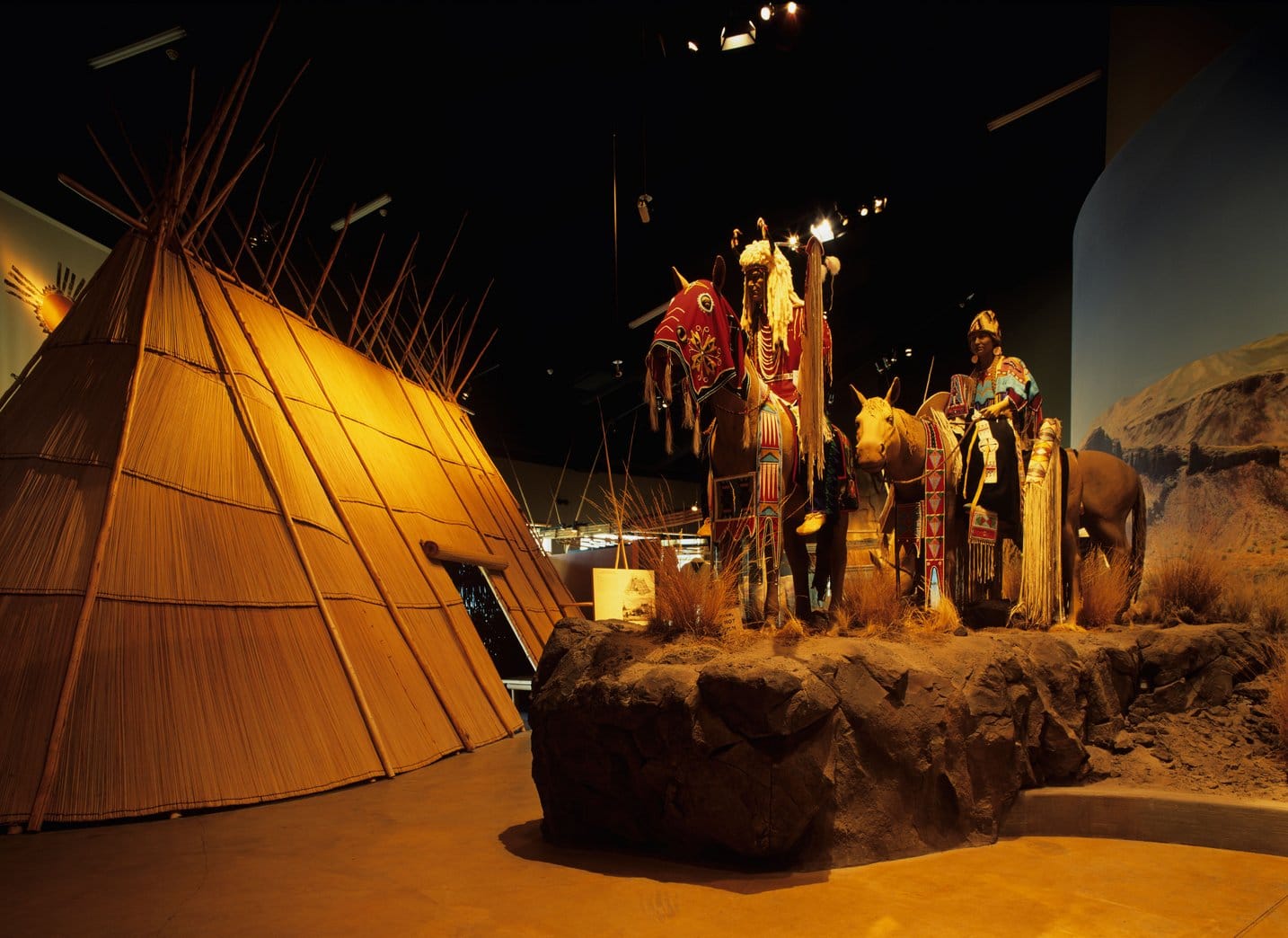

First Inhabitants & First Foods

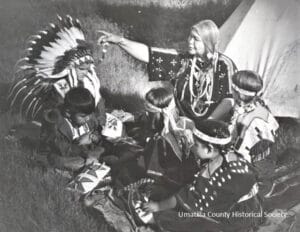

Photo provided by Umatilla County Historical Society

The traditional culture of the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla Tribes is based on a yearly cycle of food and medicine gathering. The homelands of these tribes, now known as southeastern Washington and northeastern Oregon, offered plentiful salmon, steelhead, trout, lamprey, mussels, many varieties of roots and berries, pronghorn, deer and elk. Local Tribal people moved seasonally and communally from the lowlands along sheltered rivers to the highlands of the Blue Mountains.

Celilo Falls or Wayam, down the Columbia River about 100 miles to the west, was the richest fishery in the West for more than 10,000 years and one of a handful of great trade centers in North America. Tribal men gaffed, netted, trapped, and speared very large and abundant fish. The long-handled dipnet and gaff hooks are still used today. In the traditional division of labor, women are responsible for the plant foods. Today, both men and women dry and can meats, fishes, roots, and berries so that the foods are available year-round.

Each annual migration eventually leads to the Blue Mountains for a variety of roots, to pick huckleberries, and to hunt for deer and elk. Moss is gathered from conifer trees and baked to preserve it to supplement other foods.

Every food Tribal people needed was provided by the earth. Ceremonies are still held on the Umatilla Reservation to honor the annual cycle of living from the winter solstice to the spring plants, spring and fall fishing, summer berries, and the fall hunting.

Today, the Tribal Farm Enterprise (TFE) farms over 12,000 acres of wheat and canola on Tribally owned and leased land. The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) also operates a native plant nursery and regulates hunting and fishing. Learn more at ctuir.org.

Agriculture’s Movers & Shakers

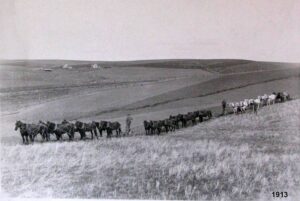

Photo provided by Frazier Farmstead Museum

Frazier, Steen, Hoon, Lee, Beauchamp, Derrick, Miller, LeFore, Pesciallo, Winn, and Rogers…all are names familiar to longtime residents of the area as people who shaped the local agricultural production and food processing industry. Some arrived in the first wagons to enter the south end of the Walla Walla valley, bringing fruit trees, seeds and farm tools from across the country. Some came after finding the Willamette Valley or California not to their liking. Others arrived later and contributed skills and finances to improving transportation and irrigation, or building canneries. The names live on in the generations that followed, with many continuing as leaders of the community.

Dig in and find out more – and possibly discover your own roots – by visiting the Frazier Farmstead Museum or FrazierFarmsteadMuseum.org.

Help From Near & Afar

The onset of World War II in Europe brought about a severe shortage of farm laborers in this area and across the country. The Federal and state governments stepped in to help farmers recruit people to tend and harvest the important crops. Organized groups of local women and children filled much of the need, but more hands and muscle were needed. State extension offices (in Oregon, operated under Oregon State College), man-aged the recruiting, training and placement of farm workers from Mexico and Jamaica. German prisoners of war being held at a POW camp along the Walla Walla River helped bring in the pea harvest. These workers and the farmers who employed them saved the bounty that would feed the nation and was critical to the successful war effort.

A Lasting Influence

Photo by TERO Estates

Over time, farms grew and production increased with the addition of irrigation pipelines and canals. The need for farm labor continued long after war veterans returned home. Migrant workers from Mexico brought their reputation for hard work and close-knit family culture to the area and many chose to stay. Today, much of the work in the fields is done by laborers who split their time between Oregon and Mexico, or by second- and third-generation residents who have made a permanent home here. Their traditions, festivals and foods have been incorporated into the local culture. Hispanic-owned businesses serve the entire community.

An Agriculture Timeline

1872: William Samuel Frazier plots the townsite of Milton to serve travelers between Pendleton and Walla Walla, WA.

1886: Milton is incorporated

1889: Freewater is split off and founded in response to strict temperance laws in Milton. Free drinking water is promised to attract residents.

1905: By the end of the season, a Salem newspaper reports 150 people are employed in three packing houses in Freewater, earning a total of $5,000 for the packing season. The paper also reports the following amounts of product were shipped from Freewater: 15,000 crates of strawberries; 2,000 crates of cherries; 5,000 crates of various berries; 7,000 lbs. of beans, peas and new potatoes; 5,000 boxes of peaches and grapes; fifteen rail carloads of watermelons, and much more of onions, prunes, apples, asparagus and mixed fruit.

1906: The first Milton Strawberry Festival is held May 30. Within three years, the event reportedly draws an estimated 15,000 attendees from throughout the region and beyond.

1907: The Walla Walla Valley Railway builds a fourteen-mile electric railway from downtown Walla Walla to the twin cities of Milton and Freewater. Fruit, wheat and dairy products are shipped between the Oregon and Washington cities.

1910s & ‘20s: Production of wheat, peas, apples, peaches, berries and vegetables in the area continues to grow, as does the town’s regional reputation as a major food producer.

1931: Interurban passenger service is discontinued as more people are traveling in automobiles. The use of the railroad for freight continues and remains important to agriculture.

1930s: P.J. Burke Canning Company builds one of the area’s largest canneries in Milton, on an exclusive spur of the railroad and becomes its largest shipper and a major employer in the town.

1943-47: The shortage of wartime farm labor, coupled with the demand for increased production to feed the war effort brings about a national program for recruiting, training, organizing and placing farm workers. Returning war veterans are also trained and given work through the program, sometimes creating new careers.

1950: A vote by residents of the two communities consolidates Milton and Freewater into one city of 3,850 residents.

1950s: Highway 11 connects Walla Walla and Milton-Freewater with Pendleton and the Interstate freeway, and therefore opens worldwide markets for growers and processors.

1950s & ‘60s: The Milton-Freewater Pea Festival draws attention to the important crop, sponsored by Roger’s Cannery.

1985: Operations of the railroad between Walla Walla and Milton-Freewater are discontinued.

1990s: The wine industry in the Walla Walla valley takes off and growing wine grapes in Milton-Freewater and the surrounding countryside proves successful. More than 35 producers use grapes grown in The Rocks District to create their premium wines.

2013: The Milton-Freewater Cinco de Mayo celebration is launched. The 2020 census shows that Hispanics or Latinos constitute just under 46% of the city’s population and play a major role in the community’s agriculture industry.

2015: A group of vintners is successful in getting The Rocks District designated an American Viticultural Area, signifying the importance of wine grape growing and wine production in the immediate area.

We thank the following individuals and organizations for their assistance in creating information panel located in Milton-Freewater: Linda Whiting and Frazier Farmstead Museum; Patricia Dawson; Umatilla County Historical Society; Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.